The Sin of Lot's Wife

Why nostalgia is actively harmful and how it is impacting how we develop our world.

Nostalgia is a tough topic to address in an average-length Substack article. Webster’s tells us that nostalgia means, “a sad pleasure experienced in recalling what no longer exists: a wistful or sentimental yearning for a return to or the return of some real or romanticized past period or some irrecoverable past condition or setting.”

There are plenty of ways we can discuss the positives and negatives of nostalgia, but today I want to talk about it in the framing of the Biblical account of Lot’s wife.

Looking Back with Lot’s Wife

I know this is a big departure from my usual content, but bear with me as we quickly talk about Lot’s wife from the usual angle you may or may not be familiar with. Lot was considered a righteous man, and G-d sent two angels to rescue Lot’s family from Sodom and Gomorrah’s pending destruction.

While fleeing the city, the angels command the party to “not look back,” and Lot’s wife (unnamed unless you consider the Jewish midrash’s naming of Ado/Edith) fails to obey this command and is turned into a pillar of salt.

Harsh penalty for simply turning around from the apocalypse! How does this apply to the design of cities and countries? Why would her nostalgia for the city she grew up in be both a sin and cause for immediate doom?

Don’t Look Down & Let Go of the Past

Two New Testament narratives complete what I regard as the Christian view of nostalgia. First, the story of Peter as a disciple and second, the story of the rich young ruler work in concert with the story of Lot’s wife (with nicer temporal outcomes).

In the story of Peter, he sees the Lord Jesus Christ walking on the water during a storm. Christ calls to him, and he initially walks out onto the water in blind faith. Eventually, his humanity reminds him that he is doing a supernatural deed, and his faith wavers, causing him to stop and nearly drown.

In the other story, we hear of a “rich young ruler” who inquires about what he must do to attain eternal life. Christ implores him to sell everything he has for a greater reward in Heaven and to follow him. The rich young ruler stops to reflect on his worldly possessions and leaves without attaining eternal life.

What do these three stories have in common?

An invitation on faith to follow what is good

Human thinking causes the momentum to stop

A nostalgia for the good of the past and a refusal of an eternal good

The key I use to connect the three is the second bullet point. When our human thinking comes into play, when we are presented with the opportunity for something good, we tend to self-sabotage based on what we remember the past being.

“This neighborhood has never had anything but single-family homes!”

“This part of town has always been affordable with access to jobs!”

“I’ve never had a problem with making friends or finding things to do!”

The past Lot’s wife remembered, the natural laws Peter’s faith eclipsed, and the route to eternal life the rich young ruler had memorized were no longer applicable. Nostalgia transports us via memories to a specific moment in time that is pleasant, but in many ways a lie that ignores the changing reality of the present.

The nostalgia of Lot’s wife would have jeopardized the entire family by pleading with them to turn back and try to claim what was no more, much like the Israelites who pined for the “good old days” of Egypt. Those days were no more! There was no going back!

How Nostalgia Cripples Dynamism

Dynamism refers to how cities grow, expand, and develop over time. Having a healthy combination of talented people, capital, amenities, infrastructure, housing, and good ideas (that become businesses, amenities, or other value-creating assets) makes cities far more dynamic than rural areas, villages, or small towns.

Institutions like colleges, world-class hospitals, and large companies can add value that has drawn people from the countryside for hundreds of years. Yet, we see the dynamism of historic megaregions such as the Bay Area and the Northeast corridor breaking in favor of emerging megaregions such as the I-85 corridor and the Texas Triangle because nostalgia is destroying the dynamism of those areas.

San Francisco, NYC, and Boston are faced with insane rents and home prices in both their core and bedroom communities, as lower-density neighborhoods seek to preserve their property values by disallowing or stymying new construction.

Silicon Valley tech titans have openly considered relocating more infrastructure to “Sun Belt” (an awful term, but we will use it this one time) cities like Austin, Miami, and Phoenix to escape high barriers to innovation and cost-of-living pressures that restrict the available in-person talent pool.

So, why do cities that were once hubs of dynamism repeat the “sin of Lot’s wife?” Because nostalgia is far easier and comforting than accepting the maelstrom of change. The relative safety of the boat was far more normal for Simon Peter than the terror of the storm. The stability provided by wealth in the ancient world was far more appealing than giving a fortune away to the poor to follow a renegade rabbi-street preacher.

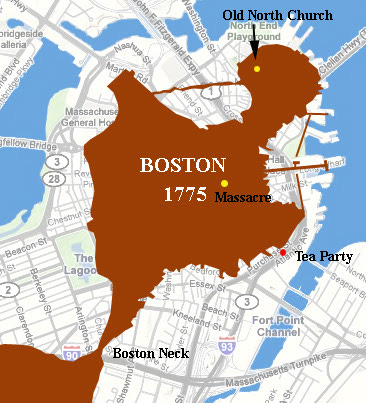

The truth is that nothing stays the same. Coastal cities like Boston and Charleston have dramatically changed since the 1700s out of necessity to increase living space, increase opportunity for trade (the deepening of Charleston harbor to 52 feet), and increase their ability to keep talented people in the area by offering new and greater non-trade opportunities.

Yes, it is great to preserve our beautiful, historical spaces, but from the time of the founding fathers to the times of the great inventors and architects of the 20th century, we have historically embraced change in our landscape.

Unfortunately, the last great change of our landscape was the destruction of many of our great neighborhoods and urban fabric with the “urban renewal” of the 1960s. Change brought highways and freeways and cars to downtowns at the cost of vibrant, walkable neighborhoods, historic buildings that were replaced by monotone memorials of what once was.

A nostalgia for the America of the 1930s, 1980s, or 2010s is misplaced as that America is no longer with us. Looking to the past is not always with nostalgia in mind, and can be useful. In a Jewish/Christian context we can look to the story of King Josiah who enacted major reforms on the rediscovery of, “the book of the Law of the Lord.”

Looking to the past in this case was not an act of “what was done back then,” but looking at the past to find solutions for the problems of the present. If we plan on building our way into a more affordable, dynamic country that will survive another 250 years, we have to abandon the nostalgia of the past for the faith of a brighter tomorrow.

Yet the Bible is clearly nostalgic for many things, like the United Monarchy (or monarchy in general), the wilderness and the Manna, G-d's miracles, even Egypt we are commanded to remember again and again. So Id suggest it's not nostalgia (even rose tinted) that is being rejected by the Tanakh but the objects which we valued improperly in the past.

This is just as true for the young ruler in the NT as it is for Lot's Wife. (Peter is interesting but I think isn't nostalgia really, more a loss of flow state).